Not Knowing: Contemporary Art and the Amateur

by Joe Scanlan

A talk given as part of a two-day conference titled “Misterio / Ministerio: La Esfera Estética Ante el Discurso del Profesionalismo” (Mystery / Administration: The Aesthetic Sphere in Light of the Discourse on Professionalism), organized by Inés Katzenstein for the Department of Art, Universidad Torcuato di Tella, Buenos Aires, April 2015.

It was a moment of serendipity when I first talked to Inés about participating in Misterio y Ministerio, because at the time I was teaching a seminar at Princeton University called “Contemporary Art and the Amateur”. The class and I had just completed our preliminary findings on the topic, so it was perfect, being invited to speak at a conference about art and professionalism.

Maybe I’m here to play the devil’s advocate, which I’m happy to do; the Donelle Woolford performance tour that Inés mentioned that was part of the 2014 Whitney Biennial is maybe proof of that. But first I wanted to say a little bit about my background. Before I started teaching at Princeton I was teaching at Yale University which was then, and remains, the top art school in the United States. Graduates include Eva Hesse, Richard Serra, Brice Marden, Matthew Barney, Wangechi Mutu, Trisha Donnelly, Kehinde Wiley… But seven years ago I was becoming quite unhappy there, in part with the kind of ‘finishing school’ that the school was becoming and more so with the kinds of students that idea was attracting.

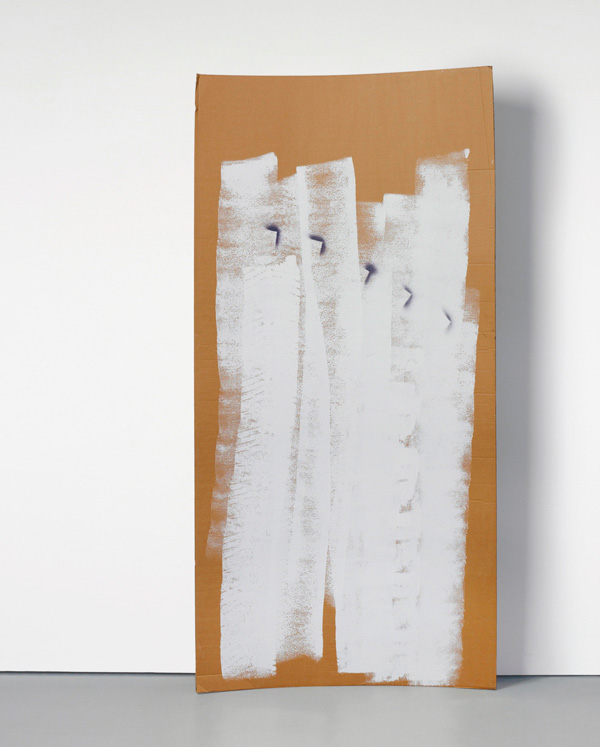

Behind me you see images of two sculptures by Gedi Sebony, an Israeli artist who lives in New York. Gedi’s profession—or shall we say, expertise—is leaning sheets of plywood against the wall. Gedi came to Yale as a visiting artist in 2008 and within two months half the students in the sculpture department were also leaning sheets of plywood against the wall. Okay; I can appreciate being influenced when something looks interesting and Gedi is an interesting artist. But in his lecture he also talked quite explicitly about how he sold this work for thirty thousand dollars and that one for forty thousand dollars… I don’t know what Sebony’s prices are now, but at the time what struck me was that none of the students were concerned that they were copying his work. When, after eight critiques in the course of a day, I said, “Are you guys noticing that this is the sixth sheet of plywood leaning against the wall that we’re looking at? Yes, it is leaning at a different angle and it is cut in a different shape, but do we need to be critical of this trend?” Their answer was a pretty flat ‘no’. They saw it as a competition: the bar had been set by Gedi Sebony, an artist who was clearly successful, and so they were all making work based on what they understood the mark of success to be at that moment. That’s how the students were approaching their education at Yale University. It wasn’t to challenge themselves or to be curious, but to put the last bit of polish on themselves before heading off to New York.

An opportunity arose for me to go to Princeton and be director of its Visual Arts Program, which was then one of the worst art schools in the country. I was interested to see what might be possible teaching art at a school where there wasn’t a clear art major, no obvious professional track, and where every person who takes an art class is in fact studying to be something else: a doctor, an anthropologist, an ORFI major—that stands for Operational Research and Finance. So I accepted the challenge and went to Princeton. I wasn’t doing it entirely naively; there are fantastic people teaching at Princeton; it’s where I got the initial inspiration to investigate this thing called “the amateur”. Because it seemed to me that, given my experience at Yale, the trained professional had nowhere to go but down. The worst thing, I would say, that can happen to an artist today is to become a professional artist.

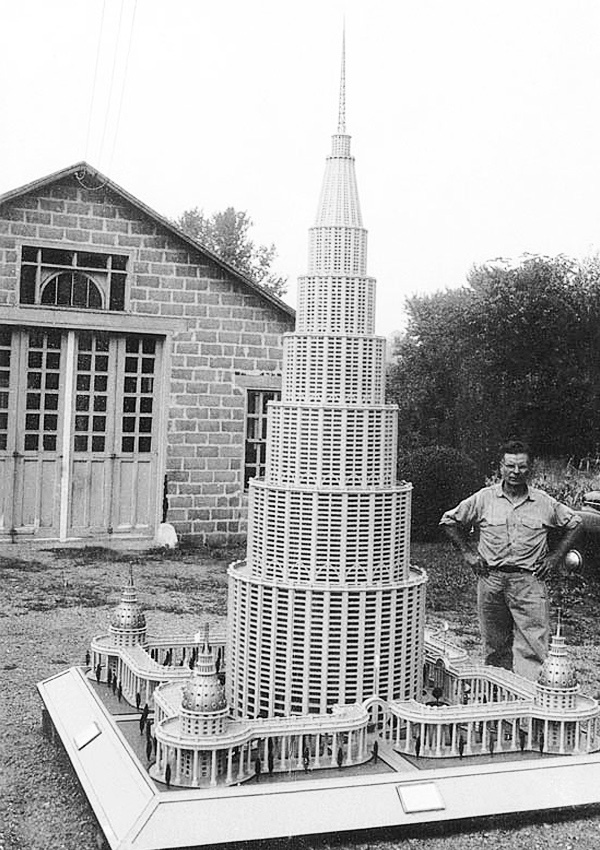

My thinking was bolstered by a panel discussion I went to on the 55th Venice Biennale, hosted by Cabinet Magazine. I didn’t go to Venice that year, but here is an installation view of a sculpture by an Italian outsider artist named Marino Auriti, titled “The Encyclopedic Palace.” Auriti had proposed that this palace be built in Washington DC and contain examples of every culture in the world, a kind of Tower of Babel for modern times. It’s a fantastic wish that Massimiliano Gioni, admirably, used as the organizing principle for the entire biennale.

My Princeton colleague, Hal Foster, was one of the commenters at the discussion. Afterward, Hal and I were talking about this sculpture, and we decided that it’s so compelling, in part, because it doesn’t anticipate its viewers and thus relieves us from the ‘fatique’ of being on guard. It is a proposal—one that will never become reality—and so in that sense it is not real. But also, as a work of outsider or amateur art, it does not project a professional savvy in the way that contemporary art has been required to do since the 1960s. Since 1968—even all the way back to Duchamp’s Fountain—there has been a gradual but increasingly oppressive requirement that artworks (and the artists who make them) be expected to know as much as possible about the artworks they make in advance of introducing them to an audience. We decided that we were tired of artists presuming to know what histories are relevant, what contexts matter, who their audience would be, and the commensurate defense mechanisms in the form of premeditated awareness that would have to be incorporated into their work. And we decided, somewhat guiltily, that it was refreshing to be able look at an artwork that demonstrated little or no awareness of these presumptions. So I had the impetus for the seminar on the amateur and, more important, a basis for appreciating this state of mind that I’ll refer to as Not Knowing.

In the seminar, we approached the idea of the amateur rather schematically and came up with five simple categories, or ‘shadings’, that I’ll go through. I hope this simplicity will leave ample open space for some vigorous questions at the end.

I’ll begin with a definition: the word amateur comes from Latin and means ‘lover of things’. For a long time in Western European culture, it was the term for someone who chose to be engaged in a particular thing without having to be expert in it or earn a living from it. Later, in the wake of The Industrial Revolution, the amateur was invoked by John Ruskin and William Morris as salvation from the dehumanization of modern society. Most recently, the amateur has become a contested status, one that is as much associated with the debased inferiority of mass entertainment as it is with the idealism of Olympic athletes. Likewise in our time, contemporary art has become contested ground, both a fertile breeding site for and the collateral damage of the contemporary affects of the amateur.

Amateur = Average

In this definition, amateur is a quality arrived at through the aggregation of diverse opinions and skills. Tino Sehgal’s work is the epitome of this algorithm and the winsome middle ground that it claims. If a professional can be defined as someone who anticipates every possible contingency that an artwork might have in advance of its audience, then Sehgal is a consummate professional. It is as if he is playing nine-dimensional chess with the institution of art, what contemporary art has become within a certain demographic. I’m completely bored with this kind of savvy, but I’m interested in the fact that everyone who participates in Sehgal’s works is an amateur, at least to the extent that they are not artists and have never performed the movements inherent to a Tino Sehgal piece in public. So Tino is a professional but his artworks are embodied by amateurs, amateurs whose ongoing participation only exalts their status.

Tania Bruguera’s Immigrant Movement International is another example of a diverse group of people’s ongoing, cumulative actions creating an affective amateur environment. This project took place two years ago in New York City with the help of the Creative Time Foundation. She opened the Immigrant Movement International (IMI) office in Queens, New York, which is the borough where the greatest concentration and variety of immigrants live. IMI functioned as a full-service community center where immigrants could work on visa issues, learn how to vote, get help finding employment, and solve housing problems. Most artworld cognescenti hated the piece because they felt Tania didn’t know what she was doing, was an insult to actual social work professionals who did, and therefore should stop embarrassing herself (and by extension the art world) by being so earnest and decadent. My counterargument would be that who Tania is, or whatever she studied in school, is not the crux of the piece. Like Tino Sehgal’s work or, more germane, the work of Rirkrit Tiravanija or Felix Gonzalez-Torres, the proof of the IMI’s effectiveness was the extent to which its audience engaged. In this respect, IMI was a proposal much in the same way that Auriti’s Encyclopedic Palace was, except that, in Bruguera’s case, the wishful thinking of IMI was based partly on the fact that, even though she built it, she didn’t know if anyone would come. In the end the project involved at least three audiences: the immigrants she hoped would join the movement; the art world; and anyone like her who was a member of both groups and thus, ideally, might serve as a bridge between the two.

Amateur = Failure

This is the category the students and I made for what you could call the classic modern amateur: The stoic. We were trying to figure out … why be an amateur? What’s the motivation? The archetype is a religious person who believes we’re all imperfect beings in the eyes of God. Conducting ourselves in a properly human manner means spending our entire lives striving for a perfection that we can never attain. That is our earthly duty and nature: to strive and fail to achieve transcendence, but keep striving anyway.

This is how the creative process was described by John Ruskin in The Nature of Gothic, the book within his larger book The Stones of Venice through which Ruskin ostensibly founded the Arts and Crafts movement. What Ruskin loved about gothic architecture is that it had no precise rules: there wasn’t a royal or international style to adhere too, nor were the stone carvers who built the churches in the 11th and 12th centuries given very precise plans. Consequently no two gothic buildings are alike and, from one to the next, you can see evidence of the architects and craftsmen figuring out what they’re doing, working to the brink of failure, and then doing a little better the next day, the next year, the next century. The promise of failure did not deter their faith, and this faith in the form of technical aspiration produced a fanatical amateur beauty.

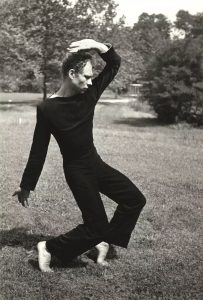

That modus operandi became our base definition of the amateur. Bruce Nauman—via Ruskin and Samuel Beckett—might be the epitome of this quasi-religious devotion to failure. Setting out to make work that is doomed from the outset but following through on it anyway because you just never know until what you’ve set out to do has been done. This is a photo document of a studio performance titled “Failing to Levitate.” Nauman is trying to achieve transcendence in the studio and it’s not working out. The demarcations on his studio floor that you can see also became the map for a series of motivations aimed at teasing out the relationships between trying and duration and failing, until exhaustion sets in, such as “Dance or Walk on the Perimeter of a Square” (1967).

What I really love about this performance, in addition to its turning studio activity into a ritualized task, is that Nauman didn’t let the then prevalent verité principle constrain the post-production of the work. When it comes to conveying meaning, veracity has its limits, so Nauman put the metronome soundtrack out of sync with the filmed movement of the piece. You not only identify with the awkward futility of the performance, you viscerally feel it as a cognitive synapse in your head. It makes you feel no more sufficient to the task of perceiving the piece than Nauman is at executing it.

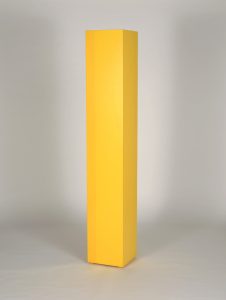

In relation to this idea I also wanted to show several works by the American artist Anne Truitt. These are all hollow wooden forms that she painted and, when she was alive, claimed that each form would tell her what color it wanted to be. The forms would emanate hues and it was her task—in a negotiation with the object—to arrive at a color that settled, satisfied, the form. Truitt was unsure if she ever did achieve that goal, but she didn’t talk about this uncertainty as quitting, or failure, but as having reached (resigned herself to) an agreement with the piece. So this object, this sculpture—I wouldn’t even say sculpture, this artwork—titled “Sunflower” (1971), might have fifty or sixty coats of paint on it, each one an attempt to achieve the right color. They’re really beautiful to look at in person. You can only see the last few coats of paint but you can feel all fifty coats in the quality, the softness, of the corners and the surface.

Ann Truitt, Sunflower (1971/1984), acrylic paint on wood

Amateur = Fallibility

We thought of this category as the ‘godless’ amateur: someone who shares an appreciation for human imperfection but without the piety that a theorist like Ruskin ascribed to it. Here the amateur makes art in an agnostic state of mind, a consciousness rooted in abandoning one’s ego and allowing contingency and chance to be your guide.

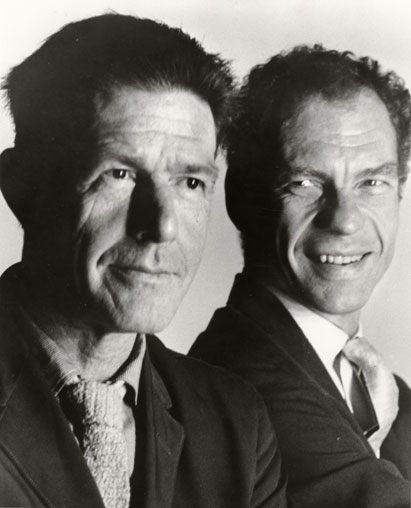

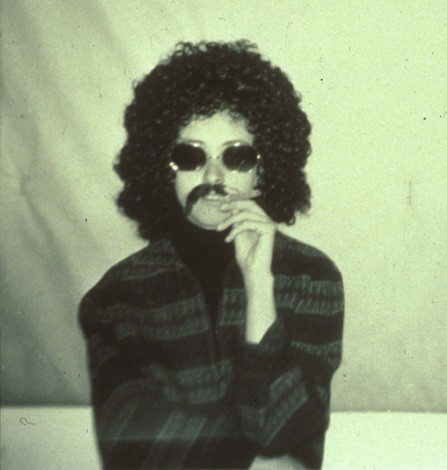

It’s always nice to see a picture of John Cage; he has such a wonderfully mischievous countenance. John Cage, you could say, is the master of the ‘fallible’ approach to art-making. Cage earned a living by giving music lessons and tutoring, among other things, and he once famously told a young student after she had completed a violin concerto for him, “You play perfectly. Now let’s see if you can do it better, and make a few mistakes.”

Photo © Hazel Larson Archer, used without permission.

This is a picture of Merce Cunningham from the late 40s, not long after he had quit the Martha Graham dance company and started his own. This was also within the four or five years when he met John Cage and the two of them started collaborating on this idea of ‘doing better by making mistakes’, so to speak, as you can see in the simple relationship of the first image of Cunningham with this one from Black Mountain College in 1952. Formally, the earlier picture clearly shows Cunningham’s virtuosity as a dancer. He was an amazing leaper, you can see that watching the early footage of him in action, but in interviews he spoke about having arrived at a moment when he became bored with being able to jump 150 centimeters into the air and wanting to see what else his body might do. He was roundly criticized at the time for that curiosity; dance critics lamenting that he was wasting his (God-given) talent. Cunningham was, in a way, embracing his fallibility and seeing what kinds of beauty it might allow.

This is an image of a beautiful piece from 1997, a choreography titled Scenario for which Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garcons designed the costumes. What I like is the way these clothes, like the choreography, limit the things that the dancers can do. Given their movements, their bodies, you can feel that they have great talent and flexibility. And so the dance, in a strange way like Ann Truitt’s work, is about the negotiation and acceptance of those limits.

Another artist we considered in this group is Sol LeWitt, and this was the one instance where the class made an artwork, LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #123, copied lines. LeWitt conceived of two hundred and fifty or so wall drawings in the course of his career. He thought of them existing like musical compositions, notes that anyone with a modicum of skill could play depending on how well the people involved could get it together. The artwork would come out accordingly. We just as well could think of them as recipes, and in that regard they have an even stronger amateur appeal. While there were certainly wall drawings that required LeWitt to maintain quality control—where he needed to sign off on it as a legitimate Sol LeWitt—others, like the one we drew, are more egalitarian. Wall Drawing #123 starts with one person drawing a vertical, freehand line down a wall as straight as possible, and the next person trying to copy it as closely as possible, and so on, by however many people there are in the group, in rotation. By the 100th or 200th line, human error and surface imperfections begin to distort the process, creating a visual ‘noise’ that only gets amplified as the drawing progresses.

Amateur = Deskilling or Disabling

This was the most contentious, or most discussed, category that we attributed to the amateur, largely because we agreed that we didn’t like the term ‘deskilling’. For better and worse, deskilling is the accepted nomenclature for a certain approach to artmaking. It is a term borrowed from business and economic theory in regards to the effects that globalized cheap labor and robotization are having on the industrialized world, that has taken hold in the art world of the past few decades as well. Instead of unionized people in Detroit earning $26 an hour making cars, there are robots and people overseas making them at a fraction of the cost.

I’ve never thought the deskilling associated with globalism was an apt corollary for what is referred to as deskilling in art. Artists are always interested in skill, and skills are the basis of what we do, whether we’re Gedi Sibony or Pierre Huyghe. Deskilling is just a misapprehension of the skills artists are developing in contradistinction to the ones that preceded them.

We chose the term ‘disabling’ instead, because it gives artists a kind of agency. To our thinking, artists aren’t victims of globalization; rather, they are resisting its forces and its ‘work ethic’ by adopting materials and narratives and time structures that require skill but counter productivity. In this way deskilling is not the annihilation of skill but the disabling of it, in the same way that Fiat Factory workers don’t stop working when they go on strike but, instead, continue working very slowly as a way of maintaining their commitment to their labor while still undermining factory output. We like the term disabling because we were interested in the potential of slowing things down because you have the know how to do it, an inverse skill that’s not inherent to the concept of deskilling. Hopefully disabling, as a term and an artistic approach, makes you aware of skills that are normally smoothed over or rendered invisible by efficiency. That efficiency, which deskilling is part and parcel of, isn’t possible when things are disabled.

This is an image of On Kawara’s current retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum. I quite like the Date Paintings because they disable time and slow it down to the point where you become aware of it as a concrete thing. If you’re On Kawara and you’re making one of these paintings, twenty-four hours could seem like a really long time; or, as he got older and less dexterous, maybe twenty-four hours went by too quickly in terms of being able to finish a painting—especially one of the larger ones. (As an aside, that’s something I’ve always wondered about the Date Paintings, whether it was harder, or took longer, to make a bigger one or a smaller one. I can imagine the intricacy of the smaller lettering being more tedious to complete that the looser strokes of the larger lettering, even though the larger ones entail covering more ground.)

One of our favorite examples of the idea of the amateur as a disabling strategy was this performance by Adrian Piper titled “The Mythic Being.” Over a series of months in New York City in the early 1970s, Piper dressed up as this “terrible demon”—the Young Black Urban Male—and walked around the streets of New York, muttering lines that she’d culled from her journals just loud enough for passersby to hear. Over the last year in particular, in the United States, this character has proven be quite a … durable myth, unfortunately … one that continues to be accosted and murdered with alarming frequency. Piper did this performance originally as a way of heightening our awareness of the misperception of this character. She wanted to disable the myth, but also to inhabit it and maybe even empower it through whatever new kinds of awareness the performance generated.

Amateur = Not Knowing

This was the last category our class devised: the idea of the amateur as someone who doesn’t know what, if anything, will result from their efforts and yet they revel in that state of not knowing. It differs from the amateur as failure in that it lacks religion, and it differs from the amateur as fallibility in that if you don’t know what you are doing then you can’t premeditate the terms of your mistakes. It has nothing in common with the algorithms of the average, but much in common with the political resistance of disabling. What was most interesting to us about this category, though, is that it can accommodate an artist like Kevin Beasley, the consummate professional young artist—a Yale sculpture grad in fact—and a wholly untrained but no less “institutionalized” artist like Judith Scott.

Kevin Beasley, performance view, Whitney Biennial (2014).

Kevin Beasley is an artist in New York City who just had a show at Kasey Kaplan Gallery. He makes sculptures that are also performance objects, objects that make sounds, but they’re quite crude—debilitated on purpose—because it puts pressure on what Beasley is able to do with them sonically and also on whether the objects in and of themselves hold our interest. Some of them are comprised of microphones buried in chunks of painted polyester resin and plaster that get rubbed, ground, banged, and otherwise coaxed into making sounds. The larger installation at Kasey Kaplan doubled as a kind of performative sculpture space in which Beasley played these instruments but also some ‘proper’ ones—an upright piano and professional mixing board—but in such a way as to dispose you of any preconceptions of what an upright piano and a mixing board might sound like. It was hard to know if anything would come of them at all, and it seemed that Beasley was no less reluctant about optimizing them. Watching Beasley perform these sculptures was like watching someone enact the metaphor of ‘getting blood from a stone’.

Judith Scott was born in Columbus, Ohio, coincidentally in the same town where I went to school, and was institutionalized as a child for having Down Syndrome. That was her life for thirty or forty years until her family moved to the west coast, where she was institutionalized again but with access to a place that provided art classes. Judith Scott, in her late fifties, was finally able to become an artist. It’s unknowable whether she was always an artist, and lived with a kind of pain until she was given an opportunity to express herself. It’s impossible to know what she knows about her production: incredibly beautiful artworks that are really bothering the professional art world, the same world in which she is becoming a star. She currently has a solo show at the Brooklyn Museum in New York. I love how we, the art world, don’t know what to do with her but maybe this category gives us a way to contextualize her work. There are many people who feel that she’s not an artist precisely because she doesn’t know what she’s doing, which is a presumptuous statement on its face. To paraphrase Ian Wilson (or Donald Rumsfeld, take your pick), no one can know what Judith Scott knows or doesn’t know, but we know Judith Scott knows something.

Amateur = Professional

Last, I want to add a bonus category to the five I have presented, and that would be the idea of the professional amateur. The professional amateur is, technically, an oxymoron, but nonetheless someone who attempts to do away with the conflict between the debased and the ideal. It is prevalent among young artists who are inspired by punk rock and DIY culture on the one hand and by drag culture, Youtube, and reality television on the other. In a way, the Yale graduate students I mentioned at the beginning of my talk, the ones spending $75,000 dollars to learn various ways of leaning sheets of plywood against the wall, are the embodiment of the professional amateur. What I took, at the time, to be a lack of criticality on their part was in fact an expression of their desire—their courage, really—to acknowledge the paradox (and absurdity) of their situation, to accept it, and even make fun of it.

There is no artist having more fun playing the role of the professional amateur right now than Ryan Trecartin. Trecartin is a young artist who lives in Los Angeles and collaborates with Lizzie Fitch, and there is a trenchant amateur quality to their work. They make films in these ambiguous, slightly sinister spaces, you can never really see where they end off camera, how big the room beyond the room is, but you get the sense of a constantly present elsewhere that doesn’t seem to matter much to the participants in the film, except that that ‘elsewhere’ is presumably where they get all the cultural data they’re riffing on. The films are streams of consciousness between Trecartin, Fitch, and their hyper-costumed and melodramatic cohorts. I can show you a clip of one film. This is Trecartin’s web space, he has a Vimeo account. This is a work called Comma Boat (2013).

I don’t know what I think about Trecartin other than that I’m happy he exists. I always find myself enjoying the films even if I’d like to think I’m not interested in their arch mannerisms. He co-curated the recent triennial at the New Museum in New York and it’s really good, a smart show, very different from his own work but sharing similar manias and anxieties, which suggests that he is more than the character of the hot young artist he has cosplayed up to now. Maybe the artist who makes his films has all been an act. You certainly get the impression that making them doesn’t hinge on our approval or disapproval of them. Not caring what anyone thinks is perhaps THE fundamental qualifying characteristic of the amateur, professional or otherwise.

Let me close by saying that the title of this talk—and much of its inspiration—is from an essay by the American fiction writer Donald Barthelme. In “Not Knowing”, Barthelme extols the necessity of not knowing both as a producer and a consumer of art. For Barthelme, not knowing is what separates art from commerce and science and journalism, not knowing is what keeps great art open to interpretation, gives it life. For Barthelme—a meticulous writer who admired both Beckett and Borges—every sentence that becomes a paragraph and every paragraph that becomes a page is constantly on the verge of spinning out of control. He writes at length, and in a mix of humility and hubris, about the experience of his fingers poised over the keyboard and having no idea what the characters in the story will do next. That state of mind is where the best, most unexpected things happen. That is the crux of not knowing and the potential freedom of being an amateur.

Thank you.

First published as “No saber: Arte Contemporanéo y Amateur,” in ¿Es El Arte un Misterio o un Ministerio?, Inés Katzenstein and Claudio Iglesias, eds., Buenos Aires: Siglio Veintiuno, 2017.