Ambulance Chasing After Culture

Chris Gilbert Interviews Joe Scanlan

Chris Gilbert was Matrix Curator at the Berkeley Museum of Art and Pacific Film Archive from 2005–2007, before he resigned in protest over a disagreement with the Museum’s board over the political framing of an exhibition he had curated: Now-Time Venezuela: Media Along the Path of the Bolivarian Process. Prior to Berkeley he was curator of contemporary art at the Baltimore Museum of Art from 2003 to 2005. He was associate curator at the Des Moines Center when this interview was conducted as part of By Design, an exhibition that took place there in Fall of 2001.

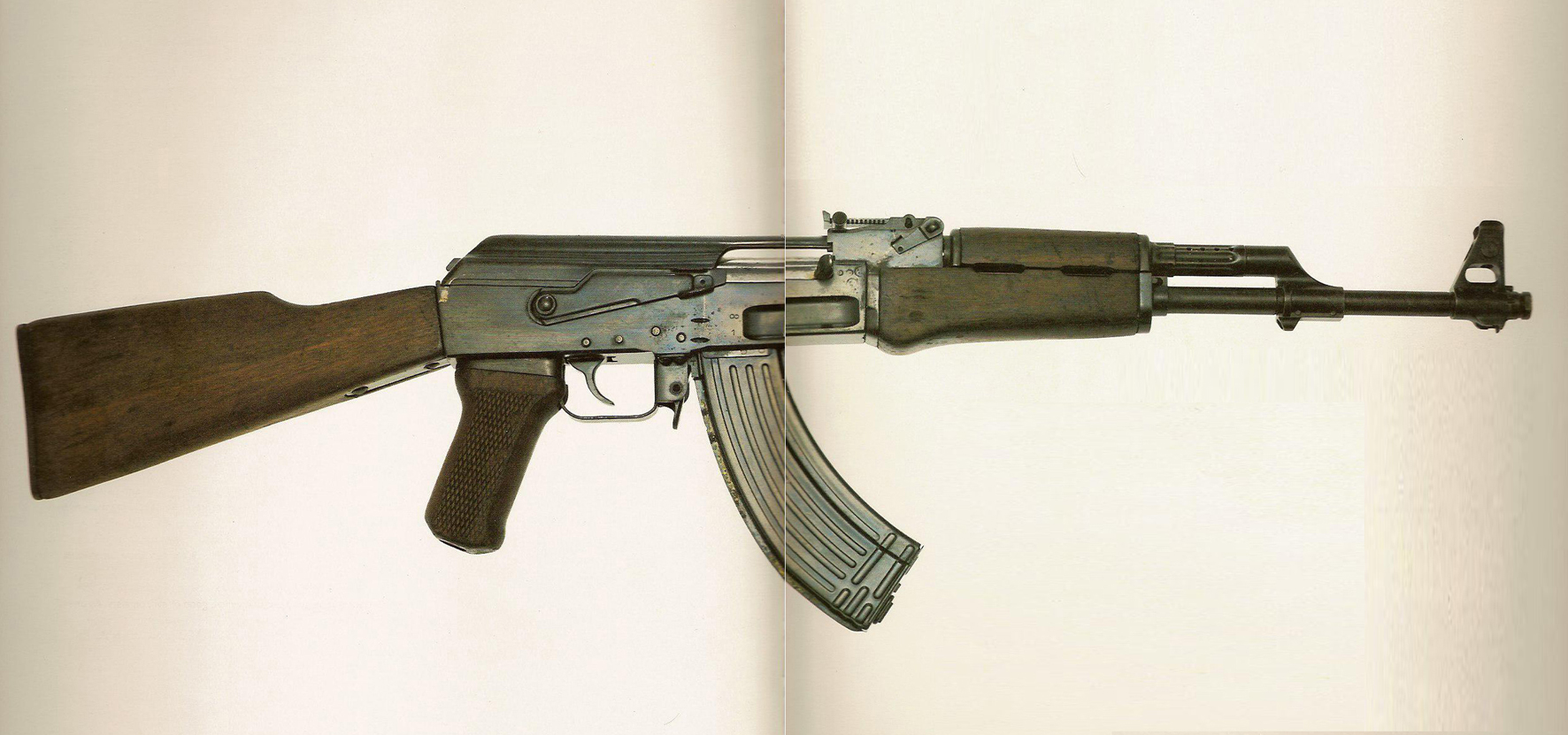

CHRIS GILBERT: I quite liked a short statement you wrote in frieze that was illustrated with an AK-47 assault rifle. It began, “Many artists today are keen on blurring the distinction between art and design, and rightfully so, since once you admit that anything is grist for the art mill, the next logical step is to design your own products as works of art.” What do you see as the historical background for this condition—everything becoming “grist for the art mill”?

JOE SCANLAN: It begins with two gestures: Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning (1911–12) and Duchamp’s Fountain (1917). The gesture of collage and the strategy of the ready-made declared that the “art mill” was open for business. Everything that has followed (Kurt Schwitters, Robert Rauschenberg, Joseph Beuys, Jeff Koons) has expanded the encyclopedia of things the art mill can digest, to the point that artists are just as fascinated with the ability of the art mill itself—the series of refining chambers that begins with the artist’s studio and runs through the gallery, the collector, the art magazine, and the museum—as they are with whatever materials they’re putting in it.

Personally, I prefer to focus on the fact that there’s another mill responsible for making things like inflatable rabbits and urinals available as raw material in the first place. That mill begins on the drafting table of some usually anonymous product designer and runs through the whole process of prototyping, fabrication, distribution and display before even having a chance of entering the public imagination. In the past decade, artists and consumers alike have become more and more interested in this other, shall we say, “ur-mill,” which begins with designers. And the more aware we become of this “ur-mill” the more appreciative we become of its own artistic greatness—from the Bauhaus and Herman Miller to Kartell and IKEA. Once you realize that there is more innovation, hubris, fantasy, and risk involved in product design than there is in contemporary art, once you realize that this is where the real cultural action is, it’s easy to start thinking that designing a great product is the best way to arrive at a work of art. Instead of making Brillo boxes you invent the Brillo pad, and things unfold from there.

CG: Let’s talk about the conceptual makeup of a product. Is something lost from the art object in order to make it more like a product, or is something added that makes it so? Perhaps the added element is the potential of a mass audience or new production methods?

JS: What is lost is the emotional guarantee that what you are making has value. A failed work of art is still a work of art. But a failed product is much more derelict, since all products contain the potential—I would say fantasy—of mass appeal. Because of this fantasy, the product not only needs an audience in order to be fulfilled, but it also has a much more precipitous fall from grace if it fails to be persuasive. Failed art is rarely part of the public imagination, but the Edsel and New Coke were great topics of derision. Compared to the public risks involved in designing products, making art is a rather safe enterprise. There’s very little at stake if you fail, and there’s not much to be gained or impressed with if you succeed.

CG: Is art, especially pop art or art that emulates modern design, just “ambulance chasing” after consumer culture?

JS: Art has been chasing ambulances ever since the Vatican hired Bernini to woo back the Protestants.

CG: Let me put it another way. In an interview you did with Amada Cruz in 1998, you drew a distinction between “talking” and “walking,” saying that ten to fifteen years ago, art tended to talk about mass culture but couldn’t actually keep pace with it. Do you think the presence of technology in the home and studio (for example, video editing software and CAD programs) might have contributed to this change, to art’s increased ability to walk with mass culture?

JS: Definitely. The U.S. government reports that one out of every five working adults today is self-employed, and some economists put the number as high as one in three. Either way, this entrepreneurial boom is partly due to the constant merging and downsizing that goes on in corporations, but it is also partly due to the fact that the technology accessible today makes it much more feasible for a person’s livelihood to be self-generated. In New York at the moment there’s an ad for a LaserJet printer whose tag line is: “Don’t let them know how small you are.” The gist is that if you buy this printer your professional image will be indistinguishable from Boeing’s or General Motors’. It’s not true, of course, but the mere acknowledgment of a desire to be indistinguishable from major corporations says a lot about the status of the individual.

For people whose primary product is digital output—graphic design, video, film, photography, drafting, publishing, music—it’s a great day. You really can make products that are technically indistinguishable from Fortune 500 products. The harder pull, the area where I think most artists are still not capable of “walking the walk,” is furniture design. Computers have greatly enhanced our ability to draw a chair, but the cost of fabricating it digitally on a scale that makes it feasible and competitive is still beyond the means of most individuals.

CG: You’ve written about democratic objects having a certain invisibility—how an object can serve its function so perfectly that you no longer see it—like the Bell 500 Series Telephones by Henry Dreyfuss. But can visibility also be part of a democratic object? If good and enfranchising design is invisible, can good and enfranchising art be about visibility or accessible beauty? I recall Michael Baxandall writing that early Italian Renaissance painting appealed to the same abilities that people at that time used in their everyday life, like judging a horse for its beauty and strength. It seems that for us a comparable ability might be looking at automobiles and looking at ranges and dishwashers and Walkmans and TVs. Might this training result in an art that relies more on “look,” or visual immediacy, rather than on theory or history?

JS: I don’t think it’s possible for an object to have immediacy without relying on theory and history. In order for something having a “look” it must reference something we’re already familiar with, be it a 1950s Formica pattern or a 1970s lapel width. Without a history of forms and our memory of them, nothing could have a look, because we wouldn’t be able to recall what the thing with the look “looked like.” As soon as we concede that the familiarity of a certain style is rooted in representation and memory, we are speaking from the standpoint of theory. For example, I can accurately say that Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon had a “look” and was visually immediate, connoting the eighteenth century, even though I was neither alive at that time nor did I see the film in its initial release. How can that be? Where did I get the information that makes Barry Lyndon seem familiar to me, and how do I trust that information? Those are theoretical questions based on historical experiences that inform my recognition of a style, no matter how immediate it may be.

CG: It seems that it is one thing for an object to be visual—to have references drawn from culture and history that determine its look—and a different matter for it to be visible and enfranchising, which is to say, seen by a large number of people.

JS: Yes, the two are distinct. I do think art can be enfranchising and thereby achieve a kind of democratic visibility. But in our time this has usually had to do with sensationalism or infamy, as with Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ (1987) or Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII (1966) at the Tate Gallery. If we said those examples followed Michael Baxandall’s model, then we would have to say those artists are appealing to the people’s everyday appetite for scandal and contempt. A more humanist example would be Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Despite the turbulence around her proposal’s ultimate approval, no one can argue with how profoundly that sculpture reflected our capacity to appreciate an unconventional form and also deem it appropriate. Ironically, the sculpture’s most distinct trait is its invisibility.

I think there is a strange shift that happens with the democratization of culture that is related both to economics and to human nature, because an artwork’s broad visibility is first accomplished through word of mouth. Word of mouth is a kind of testimonial that, depending on how much we trust our source, tells us that a certain artwork or image or product actually lives up to its billing. Having a relatively narrow distribution network, an artwork can achieve a broad visibility only after it’s achieved a broad audibility. We hear about it or read about it first, and then want to see it.

CG: That sounds like a testimonial for criticism as a means to appreciate visual art. What about theory? Does it factor into the interest in merging art and design?

JS: It does, but in a backward sort of way. In the early 1990s there was a common refrain that the public “didn’t get” contemporary art, the presumption being that they lacked the sensitivity to discern it, the knowledge to understand it, or the attention span to be challenged by it. I think the truth is to the contrary: I think the general public has “gotten it” all too well. Having been presented with such concepts as the end of originality, the pernicious relationships between art and language and commerce and desire, the occasional need for art to be less precious and more diverse—many fans of art left the galleries and museums to conduct their own cultural anthropology. For five decades art had been saying that the viewer completes the work, and whaddaya know? They went off and did.

I think that relates to what we were saying before, about our increasing aesthetic appreciation of the “ur-mill” of popular culture and what technology has made possible. We don’t need art to transform the world into art for us, we can discern our own worlds and appreciate them as art. In a way, that’s what design artists are doing: they’re processing history, thinking about the Bauhaus and Dada and Robert Ryman and Sherrie Levine, thinking about function and material and surface and content. But instead of those thoughts being manifested in conventional art forms, they’re being manifested as applied design.

Here is a collection of essays on the relationships between art and design.

Here is some related content.