Confessions of the Century

Foreword

Work, or the absence of it, was a lifelong concern for Marcel Broodthaers. It effected his principles as an artist, his politics as a citizen, and squared with his early, chosen occupations of poet, activist, bookseller, tour guide, bank teller, and freelance writer /photo-journalist. This last tandem suited Broodthaers well: he was a detached but keen observer of humanity, had a flair for droll insight, and was apparently able to meet the deadlines of the mainstream press. Throughout the latter half of the 1950s, Broodthaers covered the London literary scene, Paris galleries, and the small-town summer festivals of the Maastricht region with equal aplomb. René Magritte considered him a sociologist.

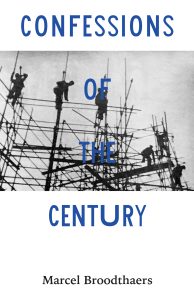

Indeed, while such assignments afforded Broodthaers the status of a paid outsider, a chronicler of communities to which he did not belong, “Confessions of the Century” strikes a more personal and introspective tone. Having gotten himself hired as a worker on a construction site for the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, Broodthaers is admittedly awestruck by the comic absurdities of manual labor. Gradually, the harsh realities of wooden planks, lead paint, and three-holed bricks inspire the not-so-young poet to contemplate his existence, to wonder whether he is happy in life and, if not, what he might do about it.

As a text, “Les Confessions du Siècle” is a bibliographical anomaly, an outlier that is both known and not known. Scholars are aware that the text was in fact published in the mainstream Buxellois weekly magazine Le Patriote Illustré on December 15, 1957, despite the fact that Gloria Moure’s Marcel Broodthaers: Collected Writings includes a version titled “Expo 58” (1957), unpublished. What no one seems to have noticed, however, is that the published version contains an additional 400+ words that are missing from the Collected Writings text. These “new” words have a different tone in that they focus on the travails of Broodthaers’ fellow workers as opposed to himself. Indeed, throughout the article Broodthaers confesses admiration for their skill and dedication, a confession that perhaps is also meant to acknowledge, finally, the centuries of exploitation, abuse, and disrespect borne by workers throughout the Modern era.

What to make of these additional words? One explanation is that they were part of the Collected Writings manuscript but, like many things Broodthaers, got separated from the main text and were lost. Another plausible explanation is that the words were tacked onto the original manuscript after it had been submitted to Le Patriote Illustré. Having myself been in similar situations regarding word counts and the vagaries of magazine publishing, the editors at Le Patriote Illustré might have found themselves in pasteup with a few blank pages in need of filling; perhaps an article had fallen through, or more or less advertising than expected had come in. In any case, needing content, they might have approached Broodthaers to see if he could add some eleventh-hour content, and he agreed.

For a mainstream magazine like Le Patriote Illustré—the Belgian equivalent of, say, the Saturday Evening Post—“Les Confessions du Siècle” takes unusual license with its accompanying photography and captions, suggesting that Broodthaers had a hand in them too. Far from being expository, the images and captions are oblique and relate to each other sequentially like an embedded visual poem. For example, an image of workmen perched on scaffolding that spans a network of concrete reinforcement rods, their silhouettes starkly outlined by a bright sky, is captioned, “des oiseaux ou des hommes?” Birds or men? On the same page, a prim woman sits on a bench reading Madame d’Aulnoy’s seventeenth-century fairy tale L’oiseau bleu. The caption reads, in full, “UN Palace, palace symbol … he opened the millet grain, however, and, to the great astonishment of everyone, withdrew a four-hundred-yard-long piece of canvas, a canvas so wonderful that all the birds, animals and fish of the Earth were painted there along with all the trees, fruits, plants, and rocks, seashells and exotic deap sea creatures, the sun, the moon, indeed, the portraits of kings and other sovereigns who reigned for a time in the world, and their subjects, with not even the smallest prank being left out. Each in their own state made up the unique character that suited them …”

By whatever means the spread came together—and however parts of it came to be lost—the coordination of text, photographs, and photo captions would seem to mark an important moment in Broodthaers becoming a visual artist, even if he doesn’t announce this new line of work for another seven years. In that sense it’s worth noticing the remunerative cunning of “Les Confessions du Siècle,” how the interrelatedness of the layout is mirrored by the overlapping activities for which Broodthaers got paid: paid for being a construction worker, paid for reporting on that work, and paid for taking a break from both of those jobs to photograph his milieu.

A threefer—nice work if you can get it. Especially if you’re a wayward thirty-three-year-old poet with thin white hands.

Joe Scanlan, Director

Broodthaers Society of America

the related exhibition

a related text