Entropy For Sale

Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp

In the United States, the greatest performers are the ones who kill themselves. Elvis. Marilyn. James Dean. Kurt Cobain. Some say this is because we feel a tragic loss of love and profound regret for the creative potential that has been wasted, all the films and music that we will never have again. Maybe so. I think these performers are the greatest because we appreciate the fact that they did us a favor. They understood that in order to be truly loved, they needed to dispose of their limited physical bodies so that their virtual images could live forever, and move freely about the world, and be in a million places at once, and never have anything to compare to except other images.

—Joe Scanlan in an interview with French critic Elisabeth Wetterwald

Americans love destruction. Since September 11, 2001, it has become ever more apparent that “things that fall” present unrivaled opportunities for emotional manipulation, economic profit, and political gain. Whether world leaders, stock prices, Martha Stewart, or the World Trade Center, each thing that falls marks a downward motion that inspires widespread speculation about its eventual rise. It is a kind of blood lust. Not for the destructive event itself, but for the profits to be made after the destruction has taken place. Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter called this cyclical capitalist drive “creative destruction.” By his definition, capitalism cannot advance without perpetually destroying itself in order to profit from its own regeneration.

This reflex has become so natural to American culture that its media, its citizens, its politicians and its stockbrokers all crave things that fall solely for the gains that are certain to follow. Even Robert Smithson, the great saint of American Art, understood that re-organizing entropy into containers for distribution and sale was not only a way to make the concept of entropy visible, but a way to profit from it as well. Just before he died, Smithson said as much when he told Moira Roth it was time for artists to stop trying to transcend the corruption of commercialism and industry and bourgeois attitudes. His current hagiographic treatment to the contrary, when Smithson drew a comparison between the rosy escapism of art or the cruddy workings of commerce, he sided with commerce.

Thus a great shift is occurring in the American psyche. Where for the past forty years we have been obsessed with the upward potential of Warholian celebrity—the belief that riches and fame can happen to anyone, and everyone will get their fifteen minutes’ worth—we are now obsessed with the downward potential of Smithsonian entropy and the belief that everyone and everything will have its fall.

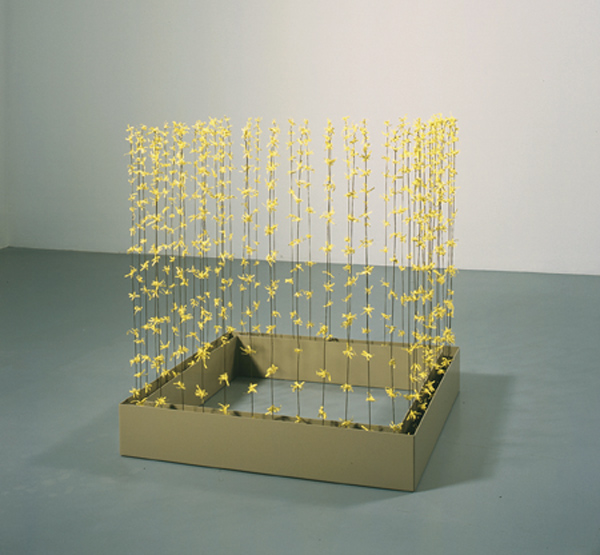

Which is not to say that America’s mood has changed, only that its profit motive has. The rise of “Smithsonomics” is not something to be sad about, it’s something to be invested in. For no matter how fucked up or chaotic or hypocritical America gets, we’ll always find a way to profit from our condition. Death! Destruction! Hurricanes! Snowflakes! Empires! Forsythia! Entropy! It’s all here, organized in nice, powder-coated aluminum bins that are pleasing to look at and easy to understand. And best of all, they’re for sale. Entropy for Sale.